A Herculean Task: Producing 3 Albums DAWlessly — Part 4

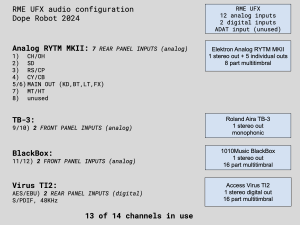

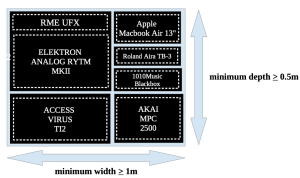

Last time, we talked about some choices that you have to make early on, which help shape where your process will go. This week, we’ll talk about the actual mixing process, where you take ideas and make full tracks out of them using the same DAWless approach used for live performances. To the right I’ve included a diagram of what my current audio routing looks like. I haven’t changed the routing at all since 2022 and very little since 2019 when I had to replace the JoMoX AirBase99 after it ran into some problems and limitations.

Sound Design, Composition & Mixing Philosophy

In most traditional music, an artist writes music and/or words and plays them on the instrument they know. But in electronic music, there is often a sound design and mixing phase as well, where you combine new sounds together, which requires a different production process. that is absent in traditional music. In addition to the songwriting process. it is also almost required to understand concepts like sound design and production topics like compression and EQ. I’m dividing what happens in this electronic music-making process into three categories: Sound design, composition, and mixing.

How Those Three Things Come Together in a Mixdown

When writing a new electronic song, you play notes into a synthesizer or DAW, and use a sequencer to record and play them back, whether ITB or not. Then you arrange those parts together, add on any other sounds or parts you want, add effects, whatever you want to do, until you’re satisfied. At some point you reach a stage where you say, “let’s record this”. That’s when you enter the mixdown phase which means you should know sound design, composing, and mixing and how to use those tools to make the best recording possible.

Let me give an example: I get to the mix stage and a drum and a bass sound are interfering and they won’t sit properly in the mix. There are essentially 3 options: change the sound or sounds, change the time that they occur, or apply processing. By thinking of decisions this way, we can divide them into the categories mentioned: Changing the sounds themselves is the “sound design” part. Moving them around in time is the “composition” part. Compression or EQ applied to the sounds after the fact is the “mixing” part. So let’s talk about how I use each of these techniques to achieve solutions in my DAWless setup.

Sound Design: Kick/Bass Interference

When a kick drum and a bass sound trigger at the same time, there is often a spike in the waveform that indicates there are overlapping frequencies that are both trying to be heard at the same time. And lets assume I like how they sound and don’t want to change the location of the notes. So there are a few options that don’t require compression. There’s the “ducking” method where the volume envelope of the bass sound is brought down just for the first part of the note. Or you can change the bass sound so that the attack of the VCA and VCF are slower. So what might you do if a kick and tom play at the same time and are interfering?

Composition: Kick/Tom Interference

Let’s say you’re building a kick and tom rhythm on the drum machine, but the kick and tom end up landing on the same note, causing a spike in the waveform. As you probably know, a kick my be “unvoiced” but there is still a fundamental note to which it corresponds. So in this case, rather than change the sounds themselves, I might move the tom over one-eighth or 1/16 of a note in either direction. I usually do this because it usually solves the problem with the added benefit of adding a new rhythmic element to the song. This is the composition solution. So what would I do to make my snare sound better?

Mixing: Snare Sounds Like Shit

So your snare isn’t really poppin’ and you want to copy the snare to a new track and pan them hard left and right? If on the RYTM, you could sample the snare and play it from an unused instrument and pan them left and right, or route the snare to both the main out and the individual out. But both of those solutions take some time and have serious drawbacks. So what I normally do to solve this problem is a “mixing” solution: set up a very short panning delay with no feedback and make sure the wet and dry sounds are at an equal level. The effect side should not have any EQ on it so it sounds as much like the original as possible. And so even though I can’t easily make copies of tracks like I do in a DAW, I’ve still more or less created what I set out to do.

So That’s How I Mix & Record DAWlessly

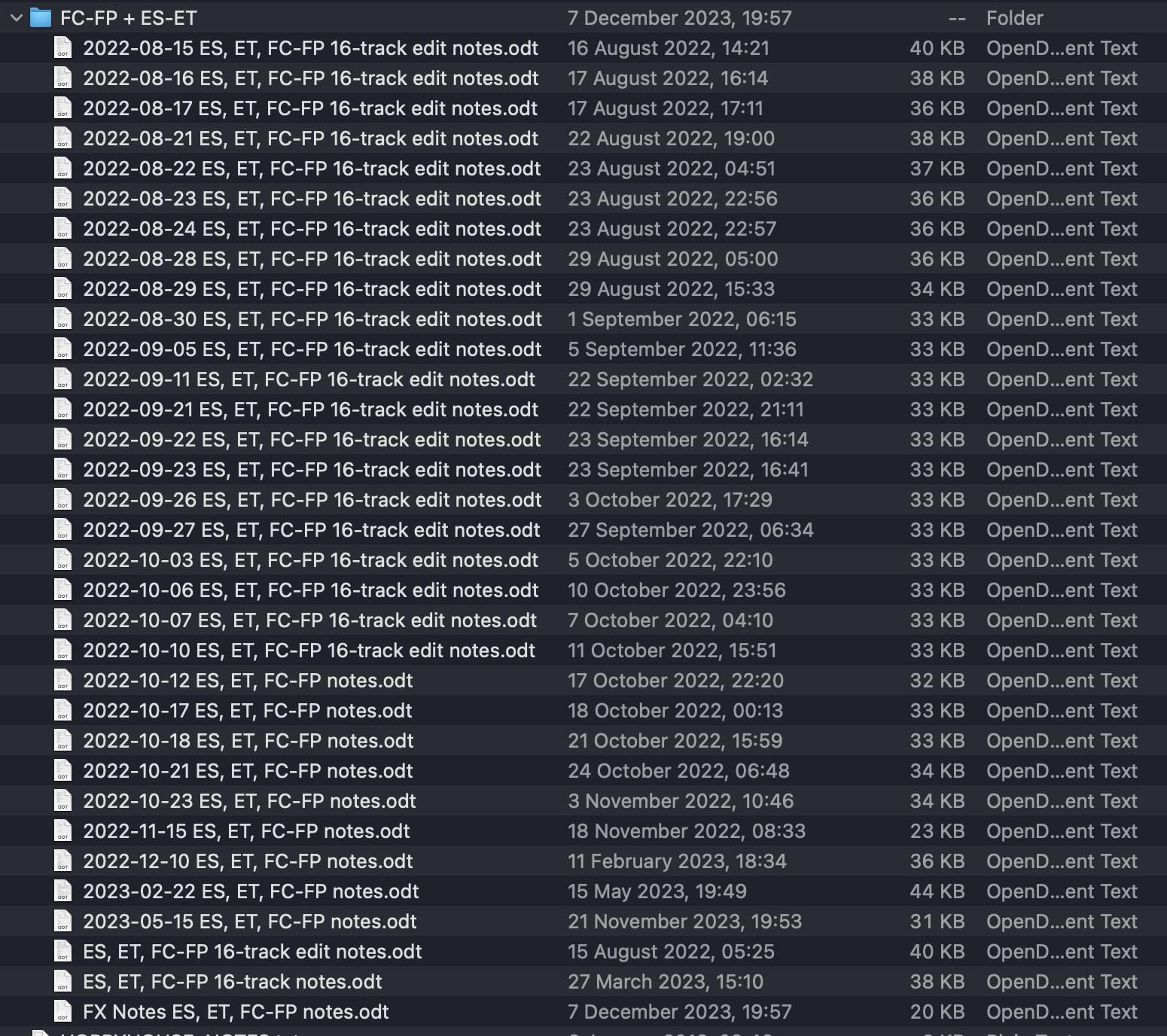

That’s my decision-making process when a song is ready to be recorded. This is where the majority of my time was spent during this process, making the decision whether to mix, compose, or sound design. That effort was much more difficult in the electro and drum n bass genres because they required lots more details and changes. I could have also stopped earlier on in the process and just let the mastering process deal with the rough edges, but I decided to work through all the issues so that they wouldn’t pop up when it came time to perform them live.